Thomas Jefferson as painted by Thomas Sully in 1821

Removal as Theory

At the final end of the American Revolution as marked by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the government of the thirteen states under the Articles of Confederation had won hypothetical control of the lands west of the Appalachians and east of the Mississippi (but the Gulf Coast remained in Spanish possession).

Indian groups still had real possession of most of this land, however, and many of those groups included strong factions that resented the forced land cessions they had already been forced to endure and would not easily give up more land to the Americans.

As we have seen, pressure to get these lands under with real American control and make them an American resource created two factions among native groups. Some we have been calling "nativists." They rejected the surrender of more land in the context of preserving traditional cultural values.

The movement of Tecumseh, Tenskwata, and the Red Sticks, among others, took this "rejectionist" approach.

On the other hand, the "accommodationists" were willing to give up some land in return for peace with the Americans and progress toward economic equality with them. The Shawnee leader Black Hoof and Cherokees such as Major Ridge should be familiar examples of people willing to deal with the Americans and adopt elements of their culture in the hope of being left alone where they were established.

Each faction had its own approach to what was, in the end, the same objective – holding on to as much land as possible with the least possible surrender of native identity.

The Americans had a different idea. At first, as with the Cherokees during and after the American Revolution, it was enough for the Americans to slice off some land while leaving the rest to the Cherokees (or perhaps just for later). But as American ambitions grew, one slice at a time would not do. The Americans wanted the whole cake.

Thomas Jefferson as painted by Thomas Sully in 1821

Thomas Jefferson suggested a way to get the whole cake while avoiding a moral catastrophe. He argued that Indians were about as intelligent as whites, but culturally backward. They could catch up, but they would have to be protected from frontier whites by removing them westward, where they could develop toward civilization without interference.

Jefferson's idea would not be implemented, however, until late in the second decade of the 19th century.

Removal from Illinois

The first targets of the removal policy were the Kickapoos in Illinois. Two treaties negotiated in 1819 called for them to move to land in Missouri Territory. About two thousand left, but about five hundred disagreed. About half the objectors gave into intimidation in 1825.

The leader of those who stayed was a religious leader, Kennekuk, also called the Kickapoo Prophet. Kennekuk had developed a set of religious ideas very close to Christianity which seems to have intrigued certain missionaries who supposed that they could bridge the gap and bring Kennekuk's followers into their folds. They were mistaken.

Kennekuk, the Kickapoo Prophet

Black Hawk

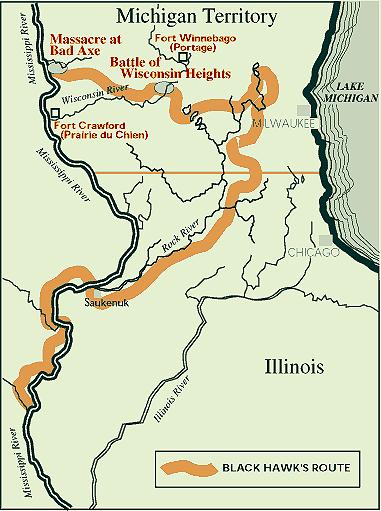

Government chiefs had sold the lands of the Sauk and Fox in Illinois without Black Hawk's consent. He and about a thousand other people returned to west central Illinois from their usual winter hunt across the Mississippi in the spring of 1832. They intended to reoccupy their town as they usually did in the spring, but found white settlers had moved in.

Meanwhile the governor of Illinois sent out the militia to put down what he took to be an Indian attack. Several companies under Major Isaiah Stillman caught Black Hawk away from his main camp with only about forty men. Outnumbered almost seven to one, Black Hawk sent out a delegation to negotiate a surrender. Stillman's men fired on the delegation and Black Hawk decided to die fighting. But when the Indians attacked the militia panicked and ran. The result was called Stillman's Run.

Major Stillman

The Americans poured men into northwestern Illinois and by August 1832 captured or killed most of Black Hawk's men. He got away but was captured later, and taken to Washington. He became a celebrity.

Pressure Mounts in the South

In the late 18th century planters in the lower South began growing cotton. After the cotton gin came into use in the late 1790s, the type of cotton they could grow became more valuable because the gin cut down the work needed to remove the seeds.

The cotton went to the new mechanized textile mills in England, and later New England. Cotton and the slavery it promoted were an essential part of the so-called Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Each mechanical invention made the work of slaves more valuable – and made Indian land in the Deep South more tempting to the rising planter class that organized and exploited the production of cotton.

From the late 18th century on the southern cotton crop roughly doubled in every decade, and by 1830 it had become the country's biggest export and the mainstay of its foreign trade.

At first the government chipped away at the southern Indian land base by sending out commissioners to make more treaties for the sale of land. Predictably, this treaty-making process caused trouble within the Indian nations as pro-treaty and anti-treaty factions formed. Relatively small groups of men accepted treaties that were opposed by their own governments.

A group of Muskogees made a treaty in 1825 in defiance of Muskogee law and the national council. Some of them escaped to the West, but those who didn't escape were executed by order of the national council.

The discovery of gold on Tsalagi land in northern Georgia in 1829 helped pressure them to remove. Miners flooded in, taking land wherever they pleased, supported by the state of George. The legislature outlawed the Tsalagi government and made it illegal for Tsagalis to mine gold on their own land.

The Removal Act

Andrew Jackson became president in 1829 on the strength of his popularity with the planters and with southern and western farmers – a popularity based partly on his record as an Indian-fighting general. Jackson was committed tp pushing removal and used his influence to get Congress to pass the Removal Act of 1830.

The act set up the machinery for the federal government to resettle the southern nations in Indian Territory. Some were prepared to accept removal, generally the people who had been most successful at adapting to white ways, with the most to lose if the nations were forced to emigrate. They hoped to save as much of their wealth as they could by cooperating.

The Choctaws in Mississippi agreed to removal almost immediately after the Removal Act went into effect, and most of them were removed by the end of 1833. They had the least distance to go, and the most familiarity with the country they were going to.

The Cherokees

The Tsagali Nation went to court to keep Georgia from enforcing its laws on Cherokee land. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case in 1831 because the Tsalagi were not a foreign nation, but what Chief Justice John Marshall called a "domestic, dependent nation."

John Ross, principal chief of the Cherokees

Two missionaries had been arrested for violating a Georgia law obliging them to swear allegiance to the state. In their case, Worcester v. Georgia, the court ruled that Georgia had no right to regulate Tsagali country, but Georgia officials ignored the decision and President Jackson refused to enforce it.

In 1835, a small group of Tsagalis led by the Ridge family held their own council at the Cherokee capital, New Echota, and signed a treaty previously rejected by the national council. Most of the nation was removed at gunpoint, after many delays, in 1838. About 4,000 people died on the way.

Robert Lindneux's painting "The Trail of Tears" (1942)

Muskogees and Chickasaws

The Muskogees gave in and signed a treaty for removal in Washington in 1832.

Like most of the removal treaties, the Washington treaty allowed individual Muskogee families to take plots of land, or allotments, in the former Muskogee nation. Many Muskogees decided to stay, but that led to conflicts with incoming whites. Federal troops rounded up the remaining Muskogees and sent them west in 1836.

The Chickasaws in northern Mississippi and northern Alabama also agreed to a removal treaty in 1832. The government complicated actual removal by insisting that the Chickasaws had to settle on land in the West that had already been given to the Choctaws. The main Chickasaw emigration didn't begin until after this complication was worked out in early 1837 by paying the Choctaws to give up part of their new territory to the Chickasaws.

The Seminoles

In 1832, Seminole leaders signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing virtually at gunpoint, but negotiated a way out by getting the government to agree that the treaty wouldn't be final until representatives of the Seminoles took a look at the land where they would be sent and reported back to the nation. Then the nation as a whole would have to consent to be moved.

In 1833, the government got representatives of the Seminoles to sign a statement which the government took to be the consent of the Seminole nation to move to Indian Territory. The government claimed the right to enforce the treaty.

The war party among the Seminoles came together around Osceola (which has been translated as Black Drink), born in Georgia in 1804 to an English father and a Muskogee mother.

Osceola

By the end of 1835 he was leading a full-scale war, the Seminole War. His followers, at most a few hundred, outmaneuvered and ran down every army sent against them until one commander offered negotiations to Osceola and then took him prisoner.

Osceola died in prison at the end of January 1838. People in the North expressed outrage.

But the war continued until 1841, costing twenty million dollars. More than fifteen hundred American soldiers were killed. About four thousand Seminoles were eventually shipped to Indian Territory. Some never did come out of the swamps, and didn't make peace with the United States until 1962.