Plagiarism

has long considered NAY MANDATED an evil in the cultural

world. Typically it has been viewed as the theft of

language, ideas, andimages

by the less than talented, often for the enhancement of personal fortune

or prestige. Yet, like most mythologies, the myth of plagiarism

is easily inverted. Perhaps it is those who support the legislation of

representation and the privatization of language

that are suspect; perhaps

the plagiarist's actions, given a specific set

of social conditions, are the ones contributing most to cultural enrichment.

Prior to the Enlightenment,plagio

was useful in aiding the distribution of ideas. An English poet could appropriate

and translate a

sonnet from Petrarch and call it his own. In

accordance with the classical aesthetic

of art(what

is art?) as imitation, this was a perfectly acceptable practice. The

real value of this activity rested less in the reinforcement of classical

aesthetics than in the distribution of Beer(or

AN IDEA) to areas

where otherwise it probably would not have appeared. The works of English

plagiarists, such as Chaucer, Shakespeare

(lmc), Spenser, Steme, Coleridge, and De Quincey,

are still a vital part of the English heritage, and remain in the literary

canon to this

day.

At present, new conditions have

emerged that once again make plagiarism

an acceptable, even crucial strategy for textual production. This is the

age of the recombinant:recombinant

bodies, recombinant gender, recombinant

texts, recombinant culture. Looking back through

the privileged frame of hindsight, one can argue that the recombinant has

always been key in the development of meaning and invention; recent extraordinary

advances in electronic

technology have called attention to the recombinant both in theory

and in practice (for example, the use of morphing

in video and film). The primary value of all electronic technology, especially

computers and imaging systems, is the startling speed at which they can

transmit information in both raw and

refined forms. As information flows at a high velocity through the electronic

networks, disparate and sometimes incommensurable systems of meaning intersect,

with both enlightening and inventive consequences. In a society dominated

by a "knowledge" explosion, exploring the possibilities of meaning in that

which already exists is more pressing than adding redundant information

(even if it is produced using the methodology and metaphysic of the "original"--thought,

is

there such a thing as an original

thought or do all ideas stem from other

ideas?). In

the past, arguments in favor of plagiarism

were limited to showing its use in resisting the privatization of culture

that serves the needs and DESIRES

of the power elite. Today one can argue that plagiarism

is acceptable, even inevitable, given the nature of postmodem existence

with its techno-infrastructure.

In a recombinant culture, plagiarism

is productive, although we need not abandon the romantic

model (the

romantic refers to a period in art history which valued individual self-expression,

the originality of the art work, and revolted against the increasing industrialization

and mechanization of Northern Europe.) of

cultural production which privileges a model of ex nihilo creation. Certainly

in a general sense the latter model is somewhat anachronistic. There are

still specific situations where such thinking is useful, and one can never

be sure when it could become appropriate again. What is called for is an

end to its tyranny and to its institutionalized cultural bigotry. This

is a call to open the cultural data base, to let everyone use the technology

of textual production to its maximum potential.

Plagiarism

is , in and of itself, diverse. With it, we can increase the rate

of progress in, as we see above, "textual production." But it is

not only in "text" that we may be able to find this act we so prejudicously

call plagriarism. What about art, motion pictures, or even computer

programming? What stops us from following the same idea with

these and other disciplines?

Ideas improve. The meaning of words

participates in the improvement. Plagiarism

is necessary. Progress implies it. It embraces an author's phrase, makes

use of his expressions, erases a false

idea, (what is a "false idea"; perhaps one that

stands alone in accordance with essentialist

notions of a text?) and replaces it with the right idea.1

Plagiarism

(lmc) often carries a weight

of negative connotations (particularly in the bureaucratic class); while

the need for its use has increased over the century, plagiarism

itself has beencamouflaged

( plagerism itself has been reinvented through the use of the internet.

Computer generated art can be altered in a way that it becomes an original

piece. This leads us into a hole new era of artist who can create a master

piece by altering someone elses artistic ideas)in

a new lexicon by those desiring to explore the practice as method and as

a legitimized form of cultural discourse.

One

way plagiarism has been camouflaged over time is by saying the exact same

thing as someone else but calling it a quote. You are still using

the same words and thoughts just saying they are someone elses. These

are not your thought and you are still using it to better something you

are trying to do. http://glamisdunes.com/ Readymades,

collage, found art or found text, intertexts, combines, detournment, and

appropriation" all these terms represent explorations in plagiarism.

Indeed, these terms are not perfectly synonymous, but they all intersect

a set of meanings primary to the philosophy and activity

of plagiarism.

Philosophically

they all stand in opposition to essentialist

doctrines of the text: They all assume that no structure within a given

text provides a universal and necessary meaning. No work of art or philosophy

exhausts itself in itself alone, in its being-in-itself. Such works have

always stood in relation to the actual life process of society from which

they have distinguished themselves. Enlightenment essentialism failed to

provide a unit of analysis that could act as a basis of meaning. Just

as the connection between a signifier and its referent is arbitrary, the

unit of meaning used for any given textual analysis is also arbitrary.

Roland Barthes' notion of the lexia

primarily indicates surrender in the search for a basic unit

of meaning. Since language

was the only tool available for the development of metalanguage,

such a project was doomed from its inception. It was much like trying to

eat soup with soup. The text itself is fluid"although the language

game of ideology can provide the illusion

of stability, creating blockage by manipulating the unacknowledged assumptions

of everyday life. Consequently, one of the main goals of the plagiarist

is to restore thedynamic and unstable drift of meaning, by appropriating

and recombining fragments of culture. In this way, meanings can be produced

that were not previously associated with an object or a given set of objects.

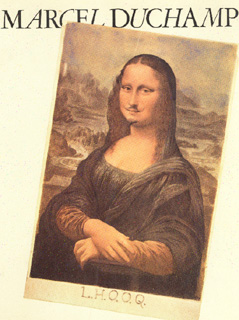

Marcel

Duchamp, one of the first to understand the power

of recombination, presented an early incarnation of this new aesthetic

with his readymade series. Duchamp tookobjects

to which he was "visually indifferent," and recontextualized them in a

manner that shifted their meaning. For example, by taking a urinal out

of the rest room, signing it, and placing it on a pedestal in an art gallery,

meaning slid away from the apparently exhaustive functional interpretation

of the object. Although this meaningdid not completely disappear, it was

placed in harsh juxtaposition to another possibility"meaning as an art

object. This problem of instability increased when problems of origin were

raised: The object was not made by an artist, but by a machine. Whether

or not the viewer chose to accept other possibilities for interpreting

the function of the artist and the authenticity of the art object, the

urinal in a gallery instigated a moment of uncertainty and reassessment.

This conceptual game has been replayed numerous times over the 20th century,

at times for very narrow purposes, as with Rauschenberg's

combines"done

for the sake of attacking the critical hegemony of Clement

Greenberg"while at other times it has been done

to promote large-scale political and cultural restructuring, as in the

case of the Situationists.Another

20th century artist, Nam Jun Paik, expresses his television technology

through the use of recombinant art. His installation known as the Cyber-Nomad

is a great example. In each case, the plagiarist works to open meaning

through the injection of scepticism into the culture-text.

Here one also sees the failure of

Romantic essentialism. Even the alleged transcendental object cannot escape

the sceptics' critique. Duchamp's notion of the inverted readymade (turning

a Rembrandt

painting into an ironing board) suggested that the distinguished

art object draws its power from a historical

legitimation process firmly rooted in the institutions of western culture,

and not from being an unalterable conduit to transcendental

realms. This is not to deny the possibility of

transcendental experience, but only to say that if it does exist, it is

prelinguistic, and thereby relegated to the privacy of an individual's

subjectivity. A society with a complex division of labor requires a rationalization

of institutional processes, a situation which in turn robs

the

individual of a way to share nonrational experience. Unlike societies with

a simple division of labor, in which the experience of one member closely

resembles the experienceof another (minimal alienation), under a complex

division of labor, the life experience of the individual turned specialist

holds little in common with other specialists. Consequently, communication

(THRU

COMMUNICATION WE ARE SHOWN THE PATH TAKEN BY THE COMPANYS CABLE THROUGH

SOME INSPIRATIONAL PARTS OF THE WORLD)

exists primarily as an instrumental function.

Plagiarism

has historically stood against the privileging of any text through spiritual,

scientific, or other legitimizing myths. The plagiarist sees all objects

as equal, a therebyhorizontalizes the plane of phenomena.

All texts become potentially usable and reusable (Nam

June Paik, (cdj). He

is fromKorea(cdj),

often called the land of the Morning Calm.

He

is fromKorea(cdj),

often called the land of the Morning Calm.  (What

is the point of the flag?)(It is a Korean

Flag Silly!) Herein lies an epistemology

of anarchy, according to which the plagiarist argues that if science, religion,

or any other social institution precludes certainty beyond the realm of

the private, then it is best to endow consciousness with as many categories

of interpretation as possible. The tyranny of paradigms may have some useful

consequences (such as greater efficiency within the paradigm), but the

repressive costs to the individual (excluding other modes of thinking and

reducing the possibility of invention) are too high. Rather than being

led by sequences of signs,

one should instead drift through them, choosing the interpretation best

suited to the social conditions of a given situation.

(What

is the point of the flag?)(It is a Korean

Flag Silly!) Herein lies an epistemology

of anarchy, according to which the plagiarist argues that if science, religion,

or any other social institution precludes certainty beyond the realm of

the private, then it is best to endow consciousness with as many categories

of interpretation as possible. The tyranny of paradigms may have some useful

consequences (such as greater efficiency within the paradigm), but the

repressive costs to the individual (excluding other modes of thinking and

reducing the possibility of invention) are too high. Rather than being

led by sequences of signs,

one should instead drift through them, choosing the interpretation best

suited to the social conditions of a given situation.

It is a matter of throwing together

various cut-up techniques in order to respond to the omnipresence of transmitters

feeding us with their dead discourses

(mass media, publicity, etc.). It is a question of unchaining the codes"not

the subject anymore"so that something will burst out, will escape; words

beneath words, personal obsessions. Another kind of word is born which

escapes from the totalitarianism of the media but retains their power,

and turns it against their old masters.

Cultural

production, literary or otherwise, has traditionally been a slow, labor-intensive

process. In painting, sculpture,

or written work, the technology has always been primitive by contemporary

standards. Paintbrushes, hammers and chisels, quills and paper, and even

the printing press do not lend themselves well to rapid production and

broad-range distribution. The time lapse between production and distribution

can seem unbearably long. Book arts and traditional

visual arts such as still suffer tremendously from this problem, when compared to the electronic

arts. Before electronic technology became dominant, cultural perspectives

developed in a manner that more clearly defined texts as individual works.

Cultural fragments appeared in their own right as discrete units, since

their influence moved slowly enough to allow the orderly evolution of an

argument or an aesthetic. Boundaries could be maintained between disciplines

and schools of thought. Knowledge

(of

self) was considered finite,

and was therefore easier to control. In the 19th century this traditional

order began to collapse as new technology began to increase the velocity

of cultural development. The first strong indicators began to appear that

speed was becoming a crucial issue. Knowledge was shifting away from

certitude and transforming itself into information. During the

American Civil War Lincoln sat impatiently by

his telegraph

line,awaiting reports from his generals at the front. He had no patience

with the long-winded rhetoric of the past, anddemanded from his generals

an efficient economy of language.

There was no time for the traditional trappings of the

still suffer tremendously from this problem, when compared to the electronic

arts. Before electronic technology became dominant, cultural perspectives

developed in a manner that more clearly defined texts as individual works.

Cultural fragments appeared in their own right as discrete units, since

their influence moved slowly enough to allow the orderly evolution of an

argument or an aesthetic. Boundaries could be maintained between disciplines

and schools of thought. Knowledge

(of

self) was considered finite,

and was therefore easier to control. In the 19th century this traditional

order began to collapse as new technology began to increase the velocity

of cultural development. The first strong indicators began to appear that

speed was becoming a crucial issue. Knowledge was shifting away from

certitude and transforming itself into information. During the

American Civil War Lincoln sat impatiently by

his telegraph

line,awaiting reports from his generals at the front. He had no patience

with the long-winded rhetoric of the past, anddemanded from his generals

an efficient economy of language.

There was no time for the traditional trappings of the

elegant essayist. Cultural velocity

and information havecontinued to increase at a geometric rate since then,

resulting in an information panic. Production and distribution ofinformation

(or any other product) must be immediate;there can be no lag time between

the two. Techno-culture

has met this demand with data bases

and electronic networks that rapidly move any type of information.

Under such conditions, plagiarism

fulfills the requirements of economy of representation, without stifling

invention. If invention occurs when a new perception or idea is brought

out"by intersecting two or more formally disparate systems"then recombinant

methodologies are desirable. This is where Plagiarism

progresses beyond nihilism.

It does not simply inject scepticism to help destroy totalitarian systerms

that stop invention; it participates in invention, and isthereby also productive.

The

genius of an inventor like Leonardo

da Vinci lay in his ability to recombine the then separate systems

of biology, mathematics, engineering, and art. He was not so much an originator

as a synthesizer. There have been few people like

him over the centuries, because the ability to hold that much data in one's

own biological memory is rare. Now, however, the technology of recombination

is available in the computer. The problem now for would-be cultural producers

is to gain access to this technology and information. After all, access

is the most precious of all privileges, and is therefore strictly guarded,

which in turn makes one wonder whether to be a successful plagiarist, one

must also be a successful hacker.What do you think

Leonardo da Vinci would think? Did you know that he wrote down all of his

ideas backwards into notebooks so that he could keep them safe from prying

eyes?WOW!!!

Oh

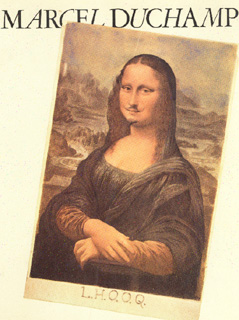

my GOD! Mona is dead!(Leonardo de Vinci,

"Mona Lisa", 1503)

Oh

my GOD! Mona is dead!(Leonardo de Vinci,

"Mona Lisa", 1503)  (Salvador Dali, "Self Portrait as Mona Lisa", 1954)

(Salvador Dali, "Self Portrait as Mona Lisa", 1954)

(Marcel Duchamp, "L.H.O.O.Q. (she's got a hot ass), 1919)

(Marcel Duchamp, "L.H.O.O.Q. (she's got a hot ass), 1919)

Most serious writers refuse to make

themselves available to the things that technology is doing. I have never

been able to understand this sort of fear. Many are afraid of using tape

recorders, and the idea of using any electronic means for literary or artistic

purposes seems to them some sort of sacrilege.

To some degree, a small portion

of technology has fallen through the cracks into the hands of the lucky

few. Personal computers and video cameras are the best examples. To accompany

these consumer items and make their use more versatile, hypertextual

and image sampling programs have also been developed"programs designed

to facilitate recombination. It is the plagiarist's dream to be able to

call up, move, and recombine text with simple user-friendly commands. Perhaps

plagiarism

rightfully belongs to post-book culture, since only in that society can

it be made explicit what book culture, with its geniuses and auteurs, tends

to hide"that information is most useful when it interacts

with other information, rather than when it is deified

and presented in

a vacuum.

Thinking about a new means for recombining

information has always been on 20th-century minds, although this search

has been left to a few

until recently. In 1945 Vannevar

Bush,(this link also has LOTS more information

on hypertext) (lmc) a former science advisor to Franklin D. Roosevelt,

proposed a new way of organizing information in an Atlantic Monthly article.

At that time, computer technology was in its earliest stages of development

and its full potential was not really understood. Bush, however, had the

foresight to imagine a device he called the Memex.

In his view it would be based around storage of information on microfilm,

integrated with some means to allow the user to select and display any

section at will, thus enabling one to move freely among previously unrelated

increments of information.

At the time, Bush's Memex could

not be built, but as computer technology evolved, his idea eventually gained

practicality. Around 1960 Theodor

Nelson made this realization when he began studying

computer programming in college:

"Over a period of months, I came

to realize that, although programmers structured their data hierarchically,

they didn't have to. I began to see the computer as the ideal place for

making interconnections among things accessible to people.

I realized that writing did not

have to be sequential and that not only would tomorrow's books and magazines

be on [cathode ray terminal] screens, they could all tie to one another

in every direction. At once I began working on a program (written in 7090

assembler language)

to carry out these ideas."

Nelson's idea, which he called hypertext,

failed to attract any supporters at first, although by 1968 its usefulnessbecame

obvious to some in the government and in defenseindustries. A prototype

of hypertext was developed by another computer innovator, Douglas Englebart,

who is often credited with many breakthroughs in the use of computers (such

as the development of the Macintosh interface, Windows). Englebart's system,

called Augment, was applied to organizing the government's research network,

ARPAnet, and was also used by McDonnell

Douglas, the defense contractor, to aid technical

work groups in coordinating projects such as aircraft design:

All communications are automatically

added to the Augment information base and linked, when appropriate, to

other documents. An engineer could, for example, use Augment to write and

deliver electronically a work plan to others in the work group. The other

members could then review the document and have their comments linked tothe

original, eventually creating a "group memory" of the decisions made. Augment's

powerful linking features allow users to find even old information quickly,

without getting lost or being overwhelmed by detail.

Computer technology(vk)continued

to be refined, and eventually"as with so many other technological breakthroughs

in) this country"once it had been thoroughly exploited by military and

intelligence agencies, the technology was released for commercial exploitation.

Of course, the development and History

of Microcomputers (vk) and consumer-grade technology

for personal computers led immediately to the need for software which would

help one cope with the exponential increase in information, especially

textual information. Probably the first humanistic application of hypertext

was in the field of education. Currently, hypertext and hypermedia

(which adds graphic images to the network of features which can be interconnected)

continue to be fixtures in instructional design and educational technology.

An interesting experiment in this

regard was instigated in 1975 by Robert

Scholes(JA) and

Andries Van Dam(JA) at Brown

University. Scholes, a professor

of English, was contacted by Van Dam, a professor of computer science,

who wanted to know if there were any courses in the humanities that might

benefit from using what at the time was called a text-editing system (now

known as a word processor) with hypertext capabilities built in. Scholes

and two teaching assistants, who formed a research group, were particularly

impressed by one aspect of hypertext. Using this program would make it

possible to peruse in a nonlinear fashion all the interrelated materials

in a text. A hypertext

is thus best seen as a web of interconnected materials.

This description suggested that there is a definite parallel between

the conception of culture-text and that of hypertext:

One of the most important facets

of literature (and one which also leads to difficulties in interpretation)

is its reflexive nature. Individual poems constantly develope their meanings"often

through such means as direct allusion or the reworking of traditional motifs

and conventions, at other times through subtler means, such as genre development

and expansion or biographical referernce"by referring to that total body

of poetic material of which the particular poems comprise a small segment.

Although itwas not difficult to

accumulate a hyperrextually linked data base consisting of poetic materials,

Scholes and his group were more concerned with making it interactive"that

is, they wanted to construct a "communal text" including not only the poetry,

but also incorporating the comments and interpretations offered by individual

students. In this way, each student in turn could read a work and attach

"notes" to it ahout his or her observations. The resulting "expanded text"

would be read and augmented at a terminal on which the screen was divided

into four areas. The student could call up the poem in one of the areas

(referred to as windows) and call up related materials in the other three

windows, in any sequence he or she desired. This would powerfully reinforce

the tendency to read in a nonlinear sequence. By this means, each student

would leam how to read a work as it truly exists, not in "a vacuum" but

rather as the central point of a progressively-revealed body of documents

and ideas.

Hyper(define

as over; in excess;exaggerated)

to exist is analogous to other forms of literary discourse besides poetry.

From the very beginning of its manifestation as a computer program, hypertext

was popularly described as a multidimensional text roughly analogous to

the standard scholarly article in the humanities or social sciences, because

it uses the same conceptual devices, such as footnotes, annotations, allusions

to other works, quotations from other works, etc. Unfortunately, the convention

of linear reading and writing, as well as the physical fact of two-dimensional

pages and the necessity of binding them in only one possible sequence,

have always limited the true potential of this type of text. One problem

is that the reader is often forced to search through the text (or forced

to leave the book and search elsewhere) for related information. This is

a timeconsuming and distracting process; instead of being able to move

easily and instantly among physically remote or inaccessible areas of information

storage, the reader must cope with cumbrous physical impediments to his

or her research or creative work. With the advent of hypertext, it has

become possible to move among related areas of information with a speed

and flexibility that at least approach finally accommodating the workings

of human intellect, to a degree that books and sequential reading cannot

possibly allow.

The recombinant text in hypertextual

form signifies the emergence of the perception of textual constellations

that have always/already gone nova. It is in this uncanny luminosity that

the authorial biomorph has been consumed.2

Barthes and Foucault may be lauded

for theorizing the death of the author; the absent author is more a matter

of everyday life,however, for the technocrat recombining and augmenting

information at the computer or at a video editing console. S/he is living

the dream of capitalism that is still being refined in the area of manufacture.

The Japanese notion of "just in time delivery," in which the units of assembly

are delivered to the assembly line just as they are called for, was a first

step in streamlining the tasks of assembly. In such a system, there is

no sedentary capital, but a constant flow of raw commodities. The assembled

commodity is delivered to the distributor precisely at the moment of consumer

need. This nomadic system eliminates stockpiles of goods. (There still

is some dead time; however, the Japanese have cut it to a matter of hours,

and are working on reducing it to a matter of minutes). In this way, production,

distribution, and consumption are imploded into a single act, with no beginning

or end, just unbroken circulation. In the same manner, the online text

flows in an unbroken stream through the electronic network. There can be

no place for gaps that mark discrete units in the society of speed. Consequently,

~notins of the origin have no place in electronic reality. The production

of the text presupposes its immediate distribution, consumption, and revision.

All who participate in the network also participate in the interpretation

and mutation of the textual stream. The concept of the author did not so

much die as it simply ceased to function. The author has become an abstract

aggregate that cannot be reduced to biology or to the psychology of personality.

Indeed, such a development has apocalyptic connotations"the fear that humanity

will be lost in the textual stream. Perhaps humans are not capable of participating

in hypervelocity.

One must answer that never has there been a time when humans were able,

one and all, to participate in cultural production. Now, at least the potential

for cultural democracy is greater. Thesingle big-genius need not act as

a stand-in for all humanity. The real concern is just the same as it has

always been: the need for access to cultural resources.

The discoveries of postmodem art

and criticism regarding the analogical structures of images demonstrate

that when two obj ects are brought together, no matter how far apart their

contexts may be, a relationship is formed. (Sergei Eisenstien called this

montage when applied to film editing. This is also present in many ideographic

languages,

where in two separate ideograms with their own meanings can form entirely

new words or meanings when brought together.) Montage is also used in terminology

relating to

propaganda

film work. Basically reenforcing

the idea that different meanings can be combined to have a symbolic meaning

for a culture (CULTURE:

"YOUR CULTURE (WHOEVER WE ARE) IS AS IMPORTANT AS OUR CULTURE (WHOEVER

WE ARE)-TIBOR KALMAN)

or people. (lmc) Restricting oneself to a personal relationship of words

is mere convention. The bringing together of two independent expressions

supersedes the original elements and produces a synthetic organization

of greater possibility.

The book has by no means disappeared.

The publishing industry continues to resist the emergence of the recombinant

text, and opposes increases in cultural speed. It has set itself in the

gap between production and consumption of texts, which for purposes of

survival it is bound to maintain. If speed is allowed to increase, the

book is doomed to perish, along with its renaissance companions painting

and sculpture. This is why the industry is so afraid of the recombinant

text. Such a work closes the gap between production and consumption, and

opens the industry to those other than the literary celebrity. If the industry

is unable to differentiate its product through the spectacle of originality

and uniqueness, its profitability collapses. Consequently, the industry

plods along, taking years to publish information needed immediately. Yet

there is a peculiar irony to this situation. In order to reduce speed,

it must also participate in velocity in its most intense form, that of

spectacle. It must claim to defend "quality and standards," and it must

invent celebrities. Such endeavors require the immediacy of advertising"that

is,full participation in the simulacra that will be the industry's own

destruction.

Hence for the bureaucrat, from an

everyday life perspective, the author is alive and well. She can be seen

and touched and traces of h/is existence are on the covers of books and

magazines everywhere in the form of the signature. To such evidence, theory

can only respond with the maxim that the meaning of a given text derives

exclusively from its relation to other texts. Such texts are contingent

upon what came before them, the context in which they are placed, and the

interpretive ability of the reader. This argument is of course unconvincing

to the social segments caught in cultural lag. So long as this is the case,

no recognized historical legitimation will support the producers of recombinant

texts, who will always be suspect to the keepers of "high" culture.

Take your own

words or the words said to be "the very own words" of anyone else living

or dead.

You will soon see that words do not belong to anyone. Words have a vitality

of their own. Poets are supposed to liberate the words"not to chain them

in phrases. Poets have no words "of their very own." Writers do not own

their words. Since when do words belong to anybody? "Your very own words"

indeed! and who are "you"?

The invention of the video portapak

in the late 1960s and early 70s led to considerable speculation among radical

media artists that in the near future, everyone would have access to such

equipment, causing a revolution in the television industry. Many hoped

that video would become the ultimate tool for distributable democratic

art. Each home would become its own production center,

and the reliance on network television for electronic information would

be only one of many options. Unfortunately this prophecy never came to

pass. In the democratic sense, video did little more than super

8 film to redistribute the possibility for image

production, and it has had little or no effect on image distribution. Any

video besides home movies has remained in the hands of an elite technocratic

class, although (as with any class) there are marginalized segments which

resist the media industry, and maintain a program of decentralization.

However,

private video artists did begin to gain some real recognition with their

work during the late 60's and

early 70's,

and with the advent of "video imaging tools," (instruments that could give

effects to what the camera was filming or

what was already

on film) these artists finally began to clain a chunk of the modern art

world for themselves. Video imaging

equipment and

the effects that it produced was the "prototype" for modern day special

effects that come standard on many

hand held cameras.

The video

revolution failed for two reasons"a lack

of access and

an absence of desire.

Gaining access to the hardware, particularly post-production equipment,

has remained as difficult as ever, nor are there any regular distribution

points beyond the local public access offered by some cable TV franchises.

It has also been hard to convince those outside of the technocratic class

why they should want to do something with video, even if they had access

to equipment. This is quite understandable when one considers that media

images are provided in such an overwhelming quantity that the thought of

producing more is empty. The contemporary, plagiarist faces precisely the

same discouragement. The potential

for generating recombinant texts at present is just that, potential.

It does at least have a wider base, since the computer technology for making

recombinant texts has escaped the technocratic class and spread to the

bureaucratic class; however, electronic cultural production has by no means

become the democratic form that utopian

plagiarists hope it will be.

The immediate problems are obvious.

The cost of technology for productive plagiarism

is still too high. Even if one chooses to use the

less efficient form of a hand-written plagiarist manuscript, desktop publishing

technology is required to distribute it, since no publishing house will

accept it. Further, the population in the US is generally skilled only

as receivers of information, not as producers. With this exclusive structure

solidified, technology and the desire and ability to use it remain centered

in utilitarian economy, and hence not much time is given to the technology's

aesthetic or resistant possibilities.

In addition to these obvious barriers,

there is a more insidious problem that emerges from the socialschizophreniaof

the US. While its political system is theoretically based on democratic

principles of inclusion, its economic system is based on the principle

of exclusion. Consequently, as a luxury itself, the cultural superstructure

tends towards exclusion as well. This economic principle determined the

invention of copyright,

which originally developed

not in order to protect writers, but to reduce competition among publishers.

In 17th-century England, where copyright first appeared, the goal was to

reserve for publishers themselves, in perpetuity, the exclusive right to

print certain books. The justification, of course, was that when formed

into a literary work,language

has the author's personality imposed upon it, thereby marking it as private

property. Under this mythology, copyright has flourished in late capital,

setting the legal precedent to privatize any cultural item, whether it

is an image, a word,

a sound or a combination

of either one. Thus the plagiarist (even of the technocratic class)

is kept in a deeply marginal position, regardless of the inventive and

efficient uses in/is methodology may have for the current state of technology

and knowledge.

What is the point of saving language

when there is no longer anything to say?

The present requires us to rethink

and re-present the notion of plagiarism.

Its function has for too long been devalued by an ideology with little

place in techno-culture.

Let the romantic notions of originality, genius, and authorship remain,

but as elements for cultural production without special privilege above

other equally useful elements. It is time to openly and boldly use the

methodology of recombination so as to better parallel the technology of

our time.

Notes

1) In its more heroic form the footnote

has a low-speed hypertextual

function"that is, connecting the reader with other sources of information

that can further articulate the producer's words. It points to additional

information too lengthy to include in the text itself. This is not an objectionable

function. The footnote is also a means of surveillance by which one can

"check up" on a writer, to be sure that he/she is not improperly using

an idea or phrase from the work of another. This function makes the footnote

problematic, although it may be appropriate as a means of verifying conclusions

in a quantitative study, for example. The surveillance function of the

footnote imposes fixed interpretations on a linguistic sequence, and implies

ownership of language and ideas by the individual cited. The note becomes

an homage to the genius who supposedly originated the idea. This would

be acceptable if all who deserved credit got their due; however, such crediting

is impossible, since it would begin an infinite regress. Consequently,

that which is most feared occurs: the labor of many is stolen, smuggled

in under the authority of the signature which is cited. In the case of

those cited who are still living, this designation of authorial ownership

allows them to collect rewards for the work of others. It must be realized

that writing itself is theft: it is a changing of the features of the old

culture-text in much the same way one disguises stolen goods. This is not

to say that signatures should never be cited; butrememberthat

the

signature

is

merely a sign,

a shorthand under

which a collection

of interrelatedideas

may

bestored and

rapidly

deployed.

2)

If the signature is a form of cultural shorthand, then it is na necessarily

honrific on occasion to sabotage the structures s' they do not fall into

rigid complacency. Attributing word to an image, i.e., an intellectual

celebrity, is inappropriat~ The image is a tool for playful use, like any

culture-text c part thereof. It is just as necessary to imagine the history

c the spectacular image, and write it as imagined, as it is t' show fidelity

to its current "factual" structure. One shoul' choose the method that best

suits the context of production one that will render the greater possibility

for interpreta tion. The producer of recombinant texts augments th language,

and often preserves the generalized code, as wine' Karen Eliot quoted Shenrie

Levine as saying, "Plagiarism?

just don't like the way it tastes."

3)

It goes without saying that one is not limited to correcting a work or

to integrating diverse fragments of out-of-date works into a new one; one

can also alter the meaning of these fragments in any appropriate way, leaving

the constipated to their slavish preservation of "citations."

(why do we as a society feel that plagiarism

is acceeptable? Will it iever end? Will this evolve to be more than the

sum of its parts? It already has, everybody's wealth of knowledge has contributed

to this document, and has created something quite unique. It is just a

shame that universities do not accept this policy on their campuses.)

epistemology:

study of origin, nature and limits of human knowledge

This document is in the process of being appropriated by

CSUSM's Fall Semester of VSAR 422 : The Art and Technology of the Moving

Image. This is a living document and is being edited constantly by its

users.

Propiedad

Registrada © 2001. Derechos

reservados mundialmente.

Copyright

© 1999. CSUSM. All rights reserved

worldwide.

h preservation of "citations."

epistemology:

study of origin, nature and limits of human knowledge

This document is in the process of being appropriated by

CSUSM's Fall Semester of VSAR 422 : The Art and Technology of the Moving

Image. This is a living document and is being edited constantly by its

users.

Copyright

© 1999. CSUSM. All rights reserved

worldwide.

still suffer tremendously from this problem, when compared to the electronic

arts. Before electronic technology became dominant, cultural perspectives

developed in a manner that more clearly defined texts as individual works.

Cultural fragments appeared in their own right as discrete units, since

their influence moved slowly enough to allow the orderly evolution of an

argument or an aesthetic. Boundaries could be maintained between disciplines

and schools of thought. Knowledge

(of

self) was considered finite,

and was therefore easier to control. In the 19th century this traditional

order began to collapse as new technology began to increase the velocity

of cultural development. The first strong indicators began to appear that

speed was becoming a crucial issue. Knowledge was shifting away from

certitude and transforming itself into information. During

still suffer tremendously from this problem, when compared to the electronic

arts. Before electronic technology became dominant, cultural perspectives

developed in a manner that more clearly defined texts as individual works.

Cultural fragments appeared in their own right as discrete units, since

their influence moved slowly enough to allow the orderly evolution of an

argument or an aesthetic. Boundaries could be maintained between disciplines

and schools of thought. Knowledge

(of

self) was considered finite,

and was therefore easier to control. In the 19th century this traditional

order began to collapse as new technology began to increase the velocity

of cultural development. The first strong indicators began to appear that

speed was becoming a crucial issue. Knowledge was shifting away from

certitude and transforming itself into information. During

Oh

my GOD! Mona is dead!(Leonardo de Vinci,

"Mona Lisa", 1503)

Oh

my GOD! Mona is dead!(Leonardo de Vinci,

"Mona Lisa", 1503)  (Salvador Dali, "Self Portrait as Mona Lisa", 1954)

(Salvador Dali, "Self Portrait as Mona Lisa", 1954)